TOKYO — Electronics makers grappling with an unprecedented global chip crunch are increasingly turning to unconventional supply channels to meet their needs — and many are getting stuck with knock-off, substandard or reused semiconductors.

Junichi Fujioka, CEO of Japanese electronics manufacturer Jenesis, has experienced this phenomenon first hand.

Unable to procure microcontrollers from its usual sources, his company’s plant in southern China placed an order through a site run by Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba. When the microcontrollers arrived, however, they failed to turn on.

An expert who examined the chips at the Tokyo-based company’s request found their specifications differed totally from what Jenesis had ordered, even though the manufacturer’s name on the packages appeared to be genuine.

Jenesis, which had already paid for the order, scrambled in vain to get in touch with the supplier.

It is a cautionary tale for electronics makers tempted to buy «chips in distribution,» a term referring to chip inventories sold by sources other than manufacturers and authorized distributors. Such chips carry no warranty from the producers and it is often unclear where and how they have been stored, which makes it easier for suspicious products to slip into orders, industry officials say.

Such products can include chips taken out of discarded electronic equipment and passed off as new, or chips that failed to meet quality standards and should have been disposed of. There are also malicious cases where the manufacturer’s name or model number on the package is falsified.

The growing prevalence of bogus chips has even spurred a new type of business.

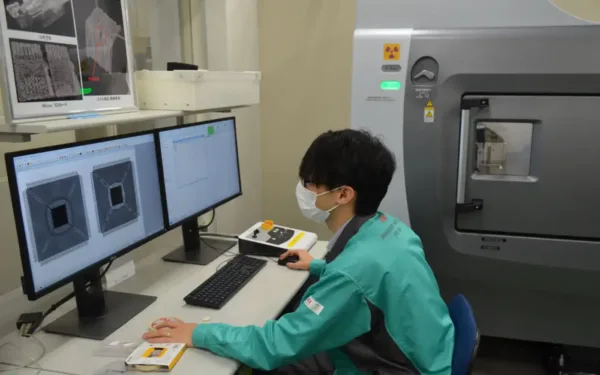

Japan’s Oki Engineering, a subsidiary of Oki Electric Industry, offers chip verification services to help electronics makers weed out faulty chips before they end up in devices.

A steady stream of questionable components flows into the company’s Tokyo offices, where nearly 20 engineers put them through a battery of tests using lasers, microscopes, X-rays and other instruments.

The inspection includes melting down the chip packages, or outer casings, to examine manufacturers’ logos, as well as looking at trace patterns on silicon chips and other physical properties.

Electronics makers are understandably desperate to secure chip supplies, since the absence of even one component can be enough to prevent them from shipping their products. But once a fake semiconductor has been assembled into a device, it is «too late» to do anything about it, warns Masaaki Hashimoto, president of Oki Engineering. «Lots of equipment makers are eager to nip defects in the bud through advance inspections,» Hashimoto said.

Oki Engineering began offering its inspection service in June and had already received some 150 inquiries as of August, with many coming from manufacturers of industrial machinery and medical equipment, the company said. After examining about 70 cases, inspectors found problematic chips in some 30% of them.

One tell-tale sign is on the outer case of a chip, or its package. Usually, a small round mark is engraved on packages to show the direction of installation. In some cases, fake products have the mark in the wrong spot, Oki Engineering said, while abnormalities in the lead frame, which connects the silicon chip to the printed circuit board, are another sign. In other cases, suppliers of fake chips change the numbers pressed into the upper part of the package to disguise the actual date of production.

A genuine chip package, above, has a round mark or index mark on the bottom left, while there is none on a fake package, below.

Oki Engineering’s service is intended «to verify the performance and reliability of semiconductors for users willing to buy from unconventional suppliers as long as their capacity is unchanged,» said Kei Takamori, head of the reliability solution department at Oki Engineering.

Before the official launch of the verification service in June, Oki Engineering had been examining the authenticity of chips at the request of individual clients. Inquiries about the work started to increase in the autumn of 2020 after the U.S. Department of Commerce restricted the export of chips using American technology to Huawei Technologies. This prompted the Chinese telecommunication equipment giant to stockpile as many chips as possible, squeezing the conventional supply chain and thus opening the door for more unconventional suppliers to step in.

In addition to the U.S-China trade war, demand for chips has boomed due to a number of factors, including increased sales of personal computers, the rise of electric vehicles and the emergence of 5G wireless technology.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., the world’s leading semiconductor maker, forecasts that the chip shortage will continue until around 2023. With that scenario looking increasingly likely, chip-hungry electronics makers have little choice but to remain vigilant.